The Vilenica jury – consisting of Aljoša Harlamov (President), Julija Potrč Šavli (Vice President), Ludwig Hartinger, Aljaž Koprivnikar, Martin Lissiach, Amalija Maček, Aleš Mustar, Tone Peršak, Gregor Podlogar, Diana Pungeršič, Jutka Rudaš and Đurđa Strsoglavec – have awarded the Vilenica 2024 Prize to Miljenko Jergović.

“Like the flame of all flames and the fire of all fires, like the final mythical ashes and dust, the fate of the Sarajevo University Library, the famous Vijećnica, whose books burned all day and all night, is not forgotten. This happened after the whistles and the explosion exactly a year ago. Perhaps on the very day you are reading this. Stroking your books gently, stranger, and remember that they are dust.”

(Sarajevo Marlboro, V. B. Z. Publishers, 2003)

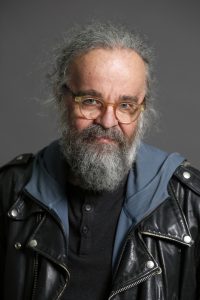

Miljenko Jergović is an author, poet, columnist, journalist, essayist, editor, journalist, literary critic and documentary filmmaker. He was born in Sarajevo in 1966, where he lived until the summer of 1993, when he left the besieged city and settled in Zagreb. An author of many identities, he is a meticulous and empathetic chronicler of turbulent, incomprehensible, terrible and beautiful times, especially in the South Slavic area. Jergović is a versatile portraitist of human destinies that have been marked by calamitous collective and personal events. He has written more than 30 works that stand at the intersection of critical and readerly taste, and he has received many national and international awards for his works.

Laudation

Prepared by Đurđa Strsoglavec, member of the Vilenica Jury

Magic Empathy

Miljenko Jergović, an author (a hypernym covering at least the following meanings: prose writer, poet, columnist, publicist, essayist, editor, journalist, literary critic, documentarist) of identity pluralism, Croatian and Bosnian, Bosnian and Croatian, a meticulous and empathetic chronicler of turbulent, inconceivable, terrible yet beautiful times mostly set in the South Slavic milieu, a broad-sweeping painter of human destinies stamped with watershed collective and private events, is one of those narrators who ‘gave to the Bosnian and Herzegovinian war story its basic tone’,[1] according to Enver Kazaz. His short story collection Sarajevski Marlboro (1994, Sarajevo Marlboro) is considered a cult book displaying the basic intention with which Jergović sets out to narrate about human destinies: the ordinary man faced with a huge, fatal event. Jergović was born in Sarajevo and lived there until the summer of 1993, when he left the city under siege and took up residence in Zagreb. Today he lives in a village near Zagreb and, in his own words, writes books and about books and walks long distances because this takes him furthest away.

The oeuvre of Miljenko Jergović is remarkable both for the sheer number of books and for their size. No account of his productivity can pass over his first prose book, the collection Sarajevo Marlboro, which explores the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina after the disintegration of the federal republic Yugoslavia (the stories were originally published in a Split daily, Nedjeljna Dalmacija, to which Jergović would send them from a besieged Sarajevo, furnished with graphics by Alem Ćurin). The last story in the collection is a dedication to the burnt-down university library of Sarajevo, as well as to all burnt-down private libraries of the Sarajevo citizens. When a library is destroyed, civilisation itself is destroyed. As a rule, short story collections are named after one of the stories – perhaps after the one with the greatest impact or with the clearest hint at the prevalent subject-matter, or by some other criterion or principle. The collection Sarajevo Marlboro, on the other hand, contains no story with this title: instead, its name is taken from a footnote in the story ‘The Gravedigger’: ‘Sarajevo Marlboro – a brand of cigarettes developed by Philip Morris Inc. to suit the taste of Bosnian smokers. The tobacco company made a study of the local cuisine before launching the product, according to a practice that is widespread in other parts of the world. That’s why Marlboro varies from country to country, and from manufacturer to manufacturer, and why a smoker can find the taste of a foreign Marlboro unpleasant. The experts from Philip Morris were especially pleased with their Sarajevo product, it seems, and believed that the tobacco in question, which grows near Gradačac and Orašje, was generally one of the better blends.’[2] The ‘key’, which enables the reader to understand the entire collection (as well as the ‘instructions’, which pave the way to understanding the historical and societal circumstances which triggered the war), is thus compressed into a footnote in one of the stories. The latter features an American journalist reporting from besieged Sarajevo, who tries to pry from a part-time local gravedigger why the war started, what is going on, who is to blame, etc., and the gravedigger cannot make him grasp that the answers are not – indeed, cannot be – unequivocal: that one should first study the context, history, milieu, habits, customs, religion, social stratification, identity problems. It is evident that the journalist has already decided how he is going to write his article – that he has already formed his opinion elsewhere rather than on the basis of his own investigation. It is the local milieu that should be explored, as it was by the Marlboro cigarette manufacturers. The novel Rod (2013, Kin) encapsulates this complexity in the following statement: ‘We can take pleasure in hatred and build our identities upon it, or we can live in a different way. When we do not hate, we see ourselves reflected in others.’[3]

It was almost three decades after Sarajevo Marlboro that there appeared the book Trojica za Kartal (2022, Three for Kartal), subtitled Sarajevo Marlboro Remastered. Again, we track human destinies marked by destruction and hate: the destinies of people in a city which was considered before the war a European Jerusalem, a city where three religions enjoyed equal status and esteem but which now harbours hate and rejection; where – to draw once more on the monumental novel Kin – ‘there is no sensation as overwhelming and fulfilling as hatred, and nothing other than hatred can go so quickly from being a private to a public emotion, one shared across a society’.[4] These stories, in which individual destinies merge into a collective voice, are phrased with the same empathy for the great destinies of ordinary people that Jergović displays in the first collection, with the same magic writing that sucks the reader in like a maelstrom – of both tears and laughter. This collection, too, consists of three parts, the only difference being the time of its production: war is always war, always equally destructive, always leaving indelible marks.

After 1994 Jergović published more short prose books, such as Karivani (1995) or Mama Leone (1999); collections of literary essays, such as Naci bonton (1998) or Historijska čitanka (2001, A Reader in History); poetry collections, such as Preko zaleđenog mosta (1996, Across the Icy Bridge) or Hauzmajstor Šulc (2001, Schultz the Repairman). He went on to demonstrate an incredible writer’s fitness by running a whole gamut of novels, starting with the almost 700-page retrospective epic Dvori od oraha (2003, The Walnut Mansion), a story about the 20th century, about its many disasters and few catharses, personal and collective, and assassinations and shipwrecks, both real and metaphorical. The book is framed by the Regina Delavale narrative, a tighly-knit even though seemingly loose framework. It was followed by the novels Gloria in excelsis (2005), Ruta Tannenbaum (2006), Srda pjeva, u sumrak, na Duhove (2007, Singing into the Twilight), Otac (2010, Father), Psi na jezeru (2010, Dogs on the Lake), Kin (2013), Doboši noći (2015, Night Drums), Wilimowski (2016), Herkul (2019, Hercules), Vjetrogonja Babukić i njegovo doba (2021, Turncoat Babukić and His Time), and Rat (2024, War). The intervals between the novels were filled with the publication of short prose, poetry and essay collections, as well as selected prose. The year 2018 marked the beginning of the Collected Works by Miljenko Jergović project, with nine books published so far.

Jergović’s texts have been translated into a number of languages inside and outside Europe. Book-length translations into Slovenian began in the year 2003, which saw the simultaneous publication of two translations of Sarajevo Marlboro as well as the translation of Mama Leone. These were followed by Slovenian versions of Buick Rivera; The Walnut Mansion; Ruta Tannenbaum; A Reader in History I and II; Singing into the Twilight; Father; Dogs on the Lake; Kin; Levijeva tkaonica svile (Levi’s Silk Weaving Mill); and most recently Three for Kartal.

Jergović’s prose most frequently and most distinctly explores the destinies and lives of those about whom ‘there was silence’ but who could be found in most Yugoslav bourgeois families; who grew up and/or spent their entire lives ‘along the tracks built by the Austro-Hungarians’, often ‘changing homes and friends’; who ‘lived in complex surroundings and a complicated linguistic web’; who were influenced by the moral and physical stance of their neighbours and recent friends ‘in the very moment of their transformation. First they would become outlaws, then murderers, and in the end martyrs, casualties of war.’ Of those who were newcomers or kuferaši, ‘suitcasers’, a nickname for ‘the people who moved to Bosnia from various parts of the empire under Franz Joseph. With their cultures and languages in tow, they had created their own extra-national identity whose cultural bedrock was stronger than their ethnic affiliation.’ Of those whose identities are not unequivocal, ‘that cannot be defined by a single word, passport, identity card, entry pass’; those whose truth is that ‘our homeland is no more, maybe never was, because for us every step and stretch of the world is foreign country’.[5]

Jergović’s fiction and non-fiction is often interspersed with autobiographic and autopoetic elements. A telling example is his 2014 essay ‘Tamni vilajet za sve je nas obećana zemlja’ (The Dark Vilayet Is the Promised Land for All of Us), prompted by a Croatian tabloid article which referred to the Islamic State as to ‘the forces of the dark vilayet’. The phrase tamni vilajet is here a politicised pejorative name for Sarajevo, or rather, for the whole Bosnia and Herzegovina with its Muslim population. The Turkish loanword vilayet denotes a higher administrative unit in the Ottoman Empire (e.g. the historical Bosnian vilayet), but in Central South Slavic languages it has also come to mean a figurative landscape, country, a zone that is in some respect special, different, specific: not simply in terms of geography but also of spirituality, mentality, word view. This is conveyed in a Balkan folk tale, ‘The Dark Country’. It tells of a ruler who arrives with his army at the end of the world and enters the dark country, eternal darkness where nothing can ever be seen. To secure his return, he prudently leaves the foals behind so that the mares would smell them, follow the scent, and thus lead himself and his army back to light. Walking through the dark country, they keep feeling underfoot something like swarming pebbles, and hear a voice in the darkness saying: ‘Whoever carries away any of these stones shall regret it. And even he who does not carry away any stones shall regret it.’ Some men think to themselves: ‘Why take the stones with me if I’m to regret it?’ Others think: ‘If I’m to regret something in any case, I might as well take a stone.’ Returning from the dark country, they see in the daylight what they had been trampling: gems, jewels, the most precious in the world. All who had not filled their pockets regretted it. But those who had filled their pockets regretted it too – because they had not taken more.

Characteristically, Jergović peppers the story of the generalised, misplaced, and pejorative use of the phrase dark vilayet with autobiographic or self-referential discouse: ‘After I left Bosnia and Sarajevo in the summer of 1993, I regretted it for a long time, for years, for a whole decade, aware at the same time that I would have regretted it as much, perhaps even more, if I had stayed. At that time Sarajevo was for me, in the full sense of the concept – a dark vilayet. You’ll regret it if you take with you the stones under your feet, and you’ll regret it if you don’t. Later I was not in the least sorry that I’d left, but I was sorry that I hadn’t gone much, much further. I would have done it if I could have met there those two or three people closest to me, as well as her, the one and the most important. But as it was not possible, we are where we are. […] As I am saying this, it is – and I mean it – the forces of the dark vilayet speaking out of me. They have nothing to do either with the Bosnian Communist bosses from the late eighties or with the Islamic State, which the USA has produced, as it has produced most of its pet enemies, to secure a place and adversary for fighting. The dark vilayet speaking out of me concerns what is most proper to a human being and what the folk genius of the Balkans has succeeded in articulating as a tale: it concerns the bitter regret that cannot be destroyed by all good fortunes of this world. According to the tale of the dark vilayet, a human being is a creature of regret.’[6]

Jergović’s style is an highly readable mixture of the gnomic and the light-hearted, of documentary weightiness and melodramatic antiqueness in the finest sense of the word. As such it calls to mind Ramon Fernandez from Marguerite Duras’ novel The Lover: ‘Ramon Fernandez used to talk about Balzac. We could have listened to him for ever and a day. He spoke with a knowledge that’s almost completely forgotten, and of which almost nothing completely verifiable can survive. He offered opinions rather than information. He spoke about Balzac as he might have done about himself, as if he himself had once tried to be Balzac. He had a sublime courtesy even in knowledge, a way at once profound and clear of handling knowledge without ever making it seem an obligation or a burden.’[7] Miljenko Jergović depicts, ‘profoundly and clearly’, a turbulent time in an even more turbulent place, portraying in this time and place ourselves as well: our wisdom of defeat, madness of victory, as runs the title of his essay collection on the metaphor of life, Mudrost poraza, ludost pobjede.

Translated by Nada Grošelj

[1] Enver Kazaz, Neprijatelj ili susjed u kući. Sarajevo: Rabic (2008), p. 83.

[2] Miljenko Jergović, Sarajevo Marlboro [trans. Stela Tomašević]. New York: Archipelago Books (2004), p. 72.

[3] Miljenko Jergović, Kin [trans. Russell Scott Valentino]. New York: Archipelago Books (2021), s. p.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Miljenko Jergović, Tamni vilajet za sve je nas obećana zemlja. https://www.jergovic.com/sumnjivo-lice/tamni-vilajet-za-sve-je-nas-obecana-zemlja/.

[7] Marguerite Duras, The Lover [trans. Barbara Bray]. London: Fontana Paperbacks (1986), p. 72.